For that boundary to remain hostile, armed, and simultaneously attractive and difficult (attractive to merchants, difficult for all) created and perpetuated exactly the weakness that cried out for exploitation by raiders from the north (coming down through the Caucusus) or from the south (coming up from Arabia). Muhammad’s heirs heeded that cry in the seventh century, and the world has not been the same since.

Imagine a strengthened Constantinople side by side with a strengthened Persia—more urbanized, more literary, more open Persia, thanks to influences from Rome in the way that Rome had earlier been enlightened by Greece. Such a pairing would have taken the world of late antiquity a good deal farther along the road to precocious globalization than has ever been imagined. The mobility of peoples, whether individuals like Cosmas or outsiders like the Huns, was already greater than it had ever been before. In the end, the traditional powers of late antique Eurasia invited themselves to be defeated by that mobility, and the invitation was accepted.

Society from the Atlantic to the Indus

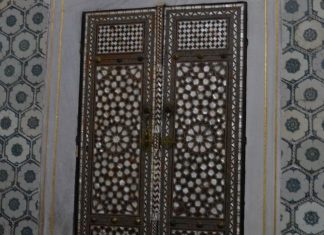

A Roman-Persian rapprochement, leading to a more open and prosperous society from the Atlantic to the Indus, would in turn have provided opportunities for more systematic and effective contacts with the Indian subcontinent and even eventually with China. What happened instead was fractious and dissipating—one new center of power in the northwest of Europe, culminating in the rise of Charlemagne; one limping Byzantine empire in its odd outpost of Constantinople; and the heart of the Middle East seized by various Islamic powers. Persia and India became outstations of that Islamic empire for many centuries, with some connections down into Africa and southeast Asia. China remained in isolation far longer than was necessary istanbul tour guide.

Second, if it was venturesome for Justinian to imagine establishing warmer relations with the shah of Persia, it was far less difficult to think of building a diplomatically successful future with the monarchs of the western Mediterranean. By Justinian’s time, a rational apportionment of lands had created stable rulers in Spain, Gaul, Italy, and Africa. For them to enter or cement a partnership with Constantinople could, would, and should have linked afresh the old territories of the Roman empire in a unity that would have been far stronger, with its distributed centers, than the overstretched and incoherent territorial unity of classical antiquity.

King of the Franks

As it was, the only one of those rulers that Justinian approached with any semblance of respect (and then mainly to create mischief for the regimes in Italy and Spain) was the one farthest from him, the king of the Franks. Once the mischief had been well and truly done and Italy was a shambles, Constantinople as good as forgot about the Franks, offering them contempt and occasional patronizing spasms of sniffy respect, until the Franks and their allies repaid the contempt in kind by pausing on their way to the Holy Land to seize Constantinople in 1204, thus reshaping the Mediterranean economy for the benefit of the Venetians. By 1400, the Byzantine empire was merely a fading city and a collection of small towns. The ruin of the Byzantine empire itself in the later middle ages was critically facilitated by its failure to make real peace and good relations with the west.

Third, peacemaking east and west would have left Justinian free for the most critical task facing him, the one he most consistently neglected: the pacification and development of his own homeland in the Balkans. We do not know Justinian’s mind well enough to understand how and why he could muster all his resources for conquest and ostentation in places where he had, truth to tell, no grounds for action, while at the same time he so consistently undermanaged, underattended to, and underdeveloped the Balkan lands of his birth. He was content to imitate his predecessors weakly, attempting with far less success than Zeno and Anastasius to play forces off against one another Christians to be a political force.

Such geopolitical wisdom may have lain beyond Justinian’s ken, I admit. Economic wisdom was demonstrably beyond him and his times, as he surveyed a capital pumped up with wealth leached away from lands no Byzantine emperor would ever again visit.